By Dani Blum

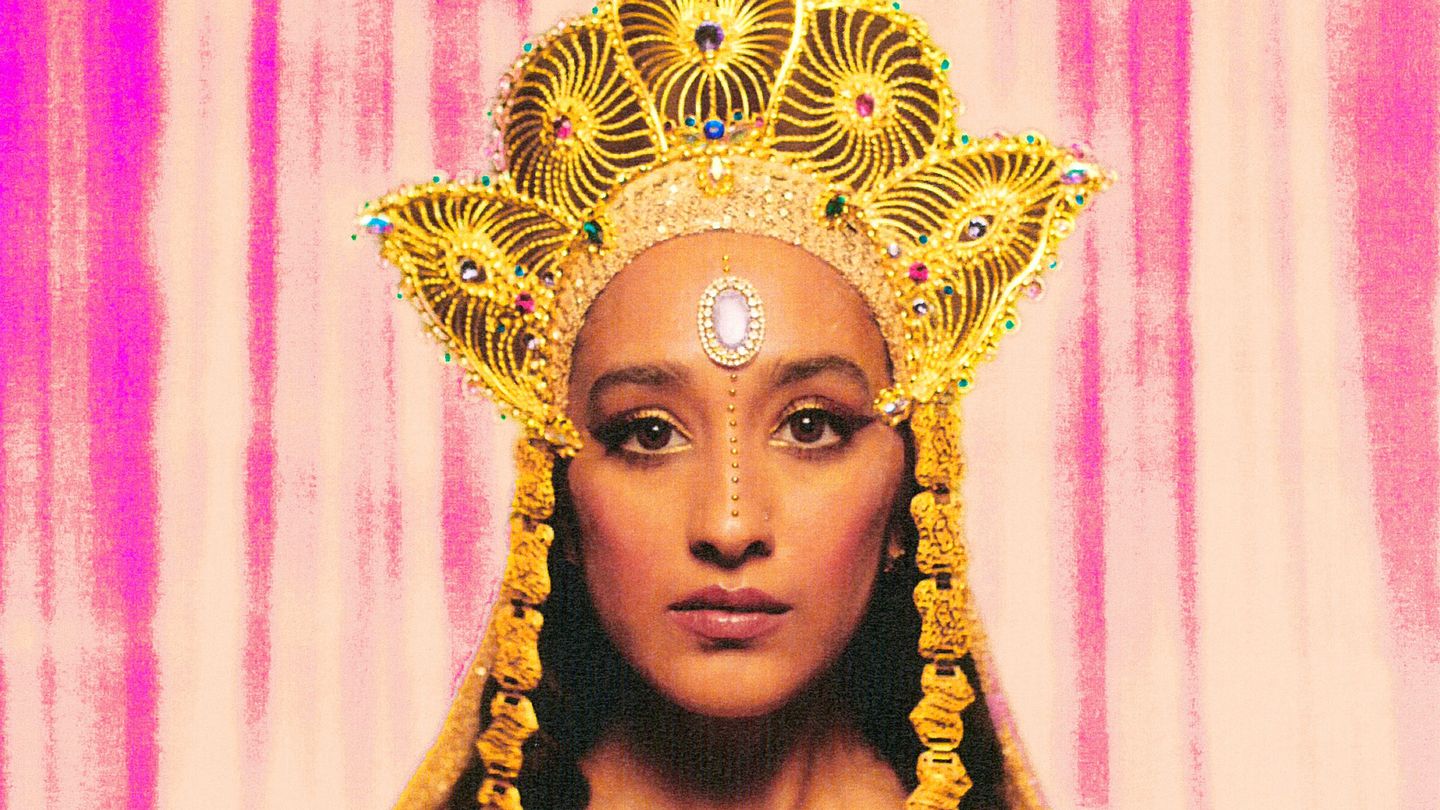

Raveena needs you to believe that you’re the only one who can heal yourself. The kaleidoscopic R&B singer-songwriter is adamant about this, anchoring her chin on her hand on the other side of the Zoom call, blinking at the bright pixels and saying, again, that nobody else can create your happiness. She knows. She’s tried.

Raveena went to the mountains every two or three days for the first stretch of quarantine in Los Angeles in 2020 and communed with aliens, or God, or both (she views these as “two sides of the same coin.”) She spends the first part of each day with 20 minutes of meditation, 20 minutes of yoga, and 5 minutes of writing down her affirmations and what she’s grateful for, a routine she developed when she got COVID-19 in December. She’s been focusing on herself, connecting to her ancestors, feeling, she says, like her soul cracked open. For the last two years, the work she’s put into her second album, Asha’s Awakening, out February 11, paralleled the work she put into herself. She weaves healing through each tingling track; she also makes a point of celebrating herself. “Our inner most self is bliss,” she says, “and bliss allows for this chaos and freedom and flow.”

The record glides through sugar-rush pop, trip-hop, Sade-inspired R&B, and spoken word intervals. The album even ends with a 15-minute long guided meditation — a move Raveena knew was risky, but she wanted the track to be a tool for her listeners. The meditations she’s found online often aren’ well-recorded, she says, and they use stock sounds; she wanted to make a high quality, well-mastered version, “top of the line produced.” Her speaking voice is steady, tranquil. (“Her voice is the type I’d expect to hear say ‘welcome to heaven’ as I hop down clouds of fluff,” reads the top comment on a video she posted of herself singing cross-legged in the grass during quarantine.) But the meditation also felt like a way to signal finding peace, the completion of a journey for the album’s titular main character.

Asha’s Awakening is a concept album that centers on a space princess from ancient Punjab, charting her revelations about love, restoration, and destruction over centuries. Raveena came up with the concept after completing six or seven songs and spending a year doing research, as she and her team studied and combed through Bollywood soundtracks. It was March 2020, and she was spiraling in the early weeks of quarantine, foraging for a way to be productive through both internal and external chaos. She had moved from New York to L.A. in the wake of a breakup, on the day the city announced shutdowns. Raveena was watching a bunch of sci-fi movies at the time, and in the span of a night, she wrote down the entire architecture for the album. A few months after, she asked an artist to illustrate Asha, so she could better grasp the character she created. For Raveena, “All the songs are personal, and then I find a way to connect it back to the story. None of the songs are really from a perspective of the character. It’s more like I could relate to the character at the end.”

Quarantine made Raveena slow down. She danced, she wrote lyrics, she put the sonic elements of songwriting on hold largely for the first six months. She would FaceTime her main guitarist, crying, and improvise songs with him while he plucked at a few chords; she called him “whenever the sobbing struck,” she says. Raveena had been working relentlessly in the years leading up to the pandemic. She started piecing together her 2017 breakout EP, Shanti, while still a student at New York University’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music. In 2019, she released “Lucid,” a cozy, curatorial album that helped propel her following. The songs she recorded then were soft, velvety, churning through trauma with grieving and grace.

Asha’s Awakening, by contrast, bursts with joy and color, almost frenetic in its tempo. This is deliberate. Healing isn’t linear, Raveena says, and sometimes it can look like this kind of chaos, the hazy process of regaining confidence in your body. “After that internal work happens, there’s a kind of life and joy that erupts from you,” she says, waving her hands in the air. “And that’s what this album really was.”

That eruption is evident in songs like “Secret,” which thumps and winds around a verse from rapper Vince Staples (she had his precise vocal tone and flow in mind for months before she even reached out to him) and the shimmering opener “Rush.” Many of these songs are psychedelic, literally; she wrote several of them following transformative acid trips. She based “Rush” on a visit she made to the Rubin Museum in New York while tripping, where she saw a sound installation with Buddhist chanting and South Asian art on the walls. “I realized that this is where I needed the next album to go,” she says. “I had to dive into my culture and intersect it with all the genres and all the art I grew up loving as a kid.”

Those connections came out of “so much historical research.” She bought eight or nine instruments from India, with no idea how to use them, and asked her bassist to figure out how to play them. They were all researching Bollywood records from the 1960s through the ‘80s, parsing the arrangements, and combing through the ways Eastern sounds inspired Miles Coltrane and the Beatles, Timbaland and M.I.A. and Jai Paul. She wanted to pay respect to the cross-cultural fusions of the past. On “Circuitboard” and “Asha’s Kiss,” which features the legendary Indian singer Asha Puthli, Raveena felt like she integrated the Bollywood influences in a way only she could, in a manner that left her mark.

Furmaan Ahmed

Furmaan Ahmed Partway through the album, the spoken word track “The Internet Is Like Eating Plastic” emerges from the twinkling soundscape. Over sinister, winking synths, Raveena murmurs like she’s dissociated or caught in a dream: “The internet makes me feel far away from my friends… The internet has me stupid and smart at the same time.” As she was writing the album, Raveena traded her iPhone for a flip phone for three months, relying on the radio and buying a GPS to help steer her way across L.A. She wanted to escape “feeling like a robot half the time,” but she also wanted to stop putting pressure on herself to put out the perfect second album. She’d been fixating on other artists’ sophomore records, and the insecurities that came with infinite scroll seemed too unhealthy to adapt to. She’d lived in the New York area for nearly her entire life, and moving to L.A. left her gasping for nature and eager to explore. Over those three, smartphone-less months, she felt her mind expand, her capacity to feel grow. She walked and walked.

These days, she’s back online, promoting her album; she flashes her iPhone at her webcam, tethered to its charger. But she takes comfort in knowing she’s capable of disconnecting and the ego death that comes with letting go. There’s a luxury in feeling small sometimes, tracing your boundaries and barriers. She laughs at the camera, dripping a curtain of hair in front of her face. “I’m just a tiny little bean on a space rock,” she says. “Trying to get through.”