Near the start of Brent Wilson’s modest, elliptical, ultimately desperately moving new documentary, the director sits Brian Wilson at a piano in his lambent Beverly Hills mansion and tosses him a few questions about his unexpectedly productive third act. “You’ve been working non-stop since your late fifties. Where did this sudden surge of creativity come from?” “Well,” says Brian, looking about as comfortable as a Californian black bear asked to explain exactly what goes on in the woods, “it starts from my brain, works its way out into the piano and then into the speakers in the studio.” “Is that something you can explain?” the director enquires, hopefully. “No,” responds Brian firmly, “I can’t.”

- ORDER NOW: Kate Bush is on the cover in the latest issue of Uncut

At this stage another film about Brian Wilson may seem less than necessary. After I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times (1995), Endless Harmony (1998), Beautiful Dreamer (2004) and 2014’s biopic Love & Mercy, it’s a story that Uncut readers will know better than most: the California childhood overshadowed by a brutally domineering father, the Beach Boys riding early-’60s surfmania into international acclaim, how Pet Sounds became Brian’s own sonic Sagrada Família before LSD shattered his beautiful mind. And then his long, dark 1970s of the soul.

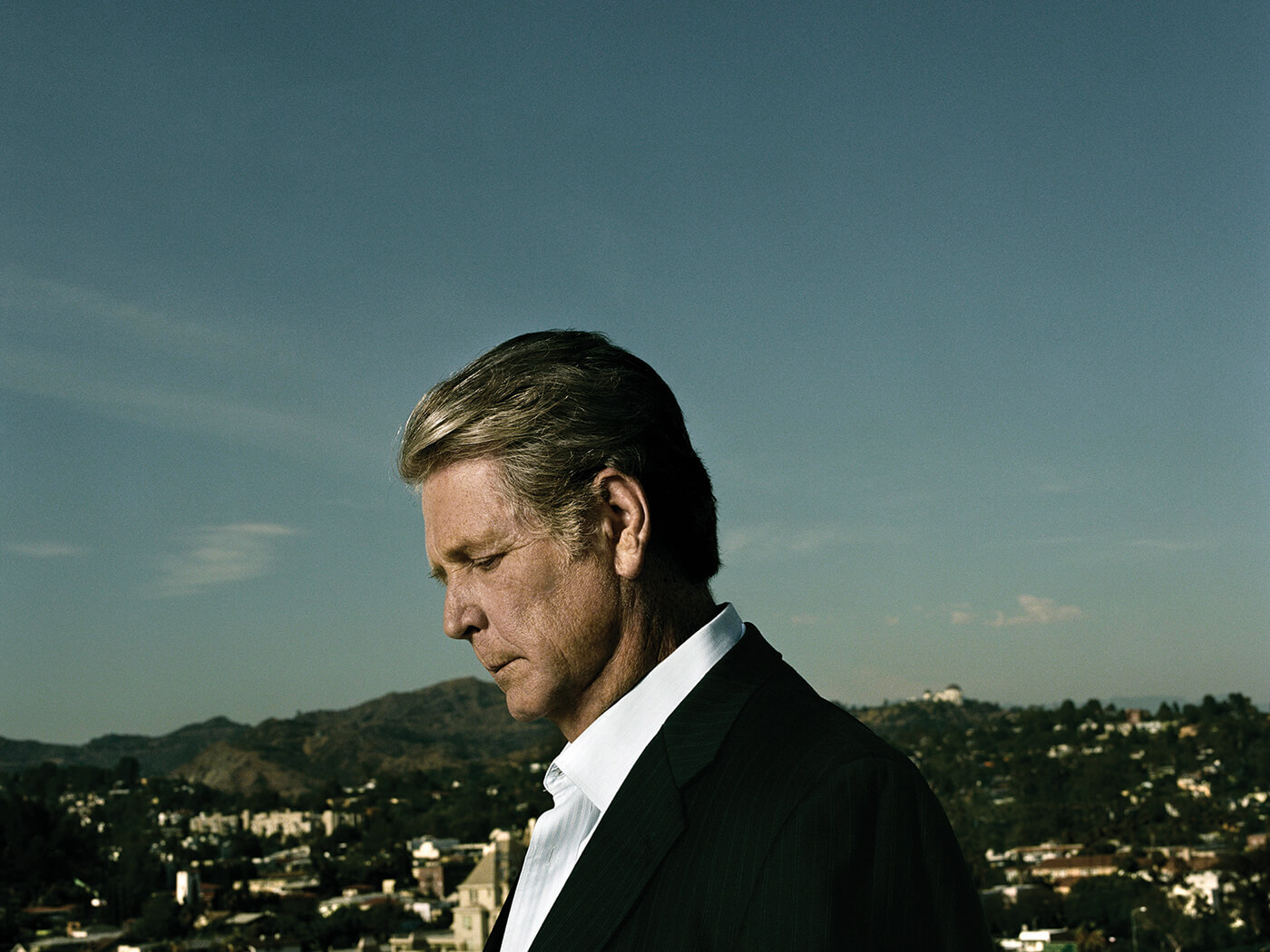

Long Promised Road pitches itself as a kind of sequel to Love & Mercy, hoping to understand how, with the love of a good woman, Brian bounced back to finish SMiLE, reform the Beach Boys and enjoy an extended victory lap. Wilson the director has a background in TV documentaries, and initially Long Promised Road feels as formulaic as a lifetime achievement reel, with the great and the good enlisted to pay homage. Springsteen and Elton both talk touchingly of the seductions of Brian’s imaginary California, while Don Was is on hand to fade up the individual channels of “Good Vibrations” with a beatific smile. But Linda Perry, Nick Jonas and the Foo Fighters’ drummer add little insight.

The film really gets going with the arrival of Rolling Stone writer Jason Fine, something of a confidant because of his calming, supportive presence. The two cruise around California through a landscape Wilson immortalised in song, from Hawthorne, through Paradise Cove and on to the Hollywood Bowl.

It’s Carpool Karaoke meets Twin Peaks: The Return. Brian, it quickly becomes clear, is still in a very fragile emotional state. As an intertitle briefly states, he has experienced auditory hallucinations since his early twenties – hearing violent and abusive voices – and in later life has been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. He seems to move through life on a precipice of panic and terror.

If nothing else, Eugene Landy’s cruel and punishing years of exploitation therapy did at least wean Brian off cigarettes, alcohol and cocaine – but now it seems he self-medicates with music. “Play “It’s OK” from 15 Big Ones,” he urgently requests every time they pass a childhood home or old haunt, and he seems overwhelmed by memories. Van Dyke Parks (one of a few key characters not involved this time round – Mike Love is also notably absent) memorably described Wilson’s music as “teenage symphonies to God”, but it’s clear they are also elaborate, fortified stain-glass structures designed

to keep the darkness out.

Eventually, after many hours on the road together, and some intriguing hints of anecdotes – Little Richard and Sly Stone visiting the Wilson compound in the mid-’70s – Fine mentions Pacific Ocean Blue, Dennis’ great, yearning 1977 solo album. Incredibly, Brian says he has never heard it. This revelation – he’s seen eyes closed, rocking back in his chair in pleasure as he listens for the first time – along with the belated news of the death of Beach Boys manager and co-writer Jack Rieley, seems to mark some emotional breakthrough for Brian. If the past has often seemed a locked room, too painful for him to enter, he’s now overwhelmed with sudden memories of love – the months in Holland, free of his father, recording fairy tales in Utrecht…

The journey comes to a conclusion at Carl Wilson’s old house and Brian can’t leave the car – “It’s just too sentimental for me.” The cameras keep rolling though – Brian alone, staring bewildered at the car stereo as it plays “Long Promised Road”, biting his lips, his eyes welling. It’s a beautiful, intrusive moment of intimacy that justifies the film: Brian’s face a rolling symphony of turmoil as he communes with his dead brothers in ancient, immortal harmonies.