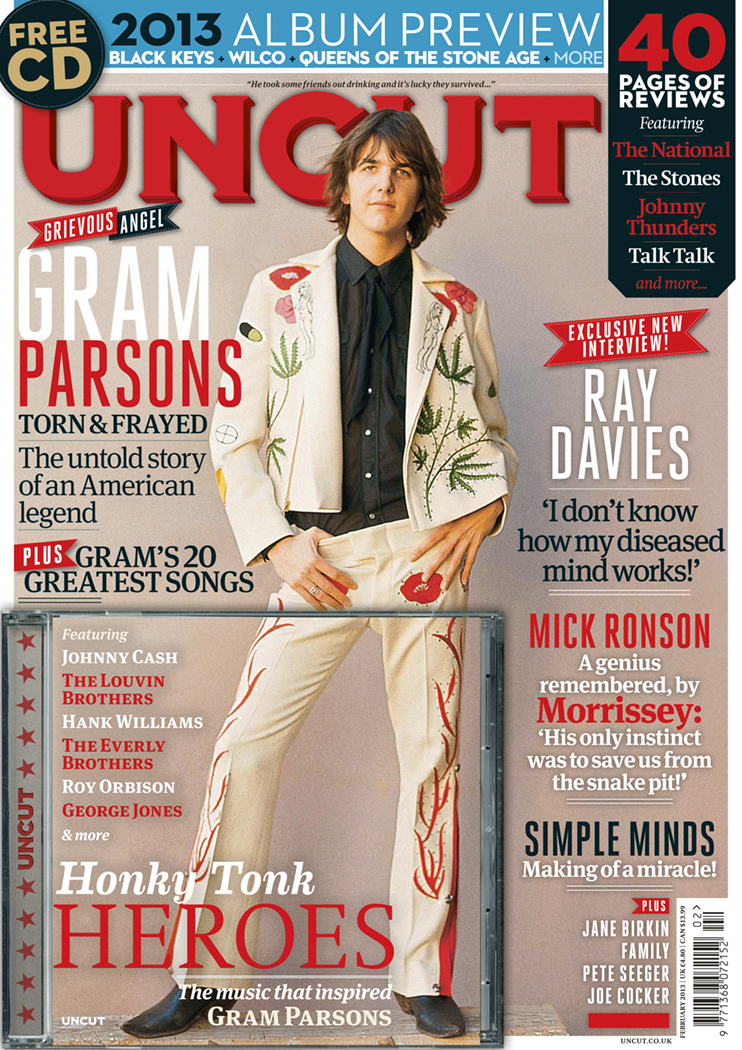

From Uncut’s February 2011 issue (Take 189). Summer 1972, GRAM PARSONS had patented his Cosmic American Music with The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers, but failed to see any of the profits. Now, thrown out of The Rolling Stones’ inner circle, he launches himself as a solo artist. On the 40th anniversary of his solo debut, Uncut’s David Cavanagh hunted down Parson’s closest collaborators to tell the untold story of an American legend’s last act…

The Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall is not the sort of place you’d expect to find Gram Parsons. Home to the southernmost tip of the British mainland, the Lizard is a remote landscape steeped in Daphne Du Maurier, shipwrecks and smugglers. But it was here that Parsons came in 1971, licking his wounds after being banished by Anita Pallenberg from Villa Nellcôte in the south of France. On the peninsula, Gram exchanged Babylonian debauchery with the Stones for peace and quiet with an old friend in a 14th-Century farmhouse.

“It’s extremely rural,” explains Ian Dunlop, Gram’s mid-‘60s comrade in the International Submarine Band, who still lives on the peninsula today. “There’s no glamour. No music industry. We’re in the hinterlands. In those days it was like Eastern Europe. The roads were miniscule. There was no M5. The A30 was a winding, asphalt-covered cart track.” Parsons, detoxing from heroin, took coastal strolls and supped pints of ale in the local pub. “England’s a place I’ve always dug for the simplicity in lifestyle,” he once said.

“There are things about Gram that people don’t understand,” insists Dunlop. “It serves the interest of myth to portray him as a decadent wastrel. But he came from a background of outdoor activity and sport. During our time in the Submarine Band, he and I would go fishing together. People like to believe that he was born with a bottle in one hand and a needle in the other. It suits their idea of the ‘persona’.”

So here was Parsons relaxing among Cornish fishermen, with his 19-year-old girlfriend Gretchen Burrell by his side. His lungs tasted fresh air: it was his career prospects that looked anaemic. The Byrds were in the past. The Flying Burrito Brothers had kicked him out. A solo album for A&M in 1970 had been abandoned. Post- Nellcôte, any hope that Keith Richards might sigh him to Rolling Stone Records – and produce his music – seemed tenuous at best. Dunlop remembers someone phoning from California one day, but otherwise there was no Parsons project on the horizon, no reason to hurry home. He was 24. Dunlop: “In hindsight he was just a little sapling.”

He had exactly two years to live.

The music made by Gram Parsons in 1972 – 73 (two studio albums and an American tour yielding a live album) was characterised by first-night nerves, reckless disregard for rehearsals and an uncanny ability to pull something special out of the hat when it mattered. The GP album (released January, 1973) and Grievous Angel (released posthumously in 1974) are pillars of Parsons’ legacy, not because they show us a country-rock trustafarian squandering his talent – although some of his former associates argue that he did precisely that – but because they reveal an unusually intimate singer facing down his demons and taking command of some truly moving material.

GP and Grievous Angel were made during bonanza years for country-rock (or Cosmic American Music, as Parsons always called it), years that witnessed bumper harvests for Neil Young, Linda Ronstadt and the Eagles. Nobody knows what the future might have held if Parsons hasn’t succumbed to an overdose of morphine and alcohol at the age of 26. “I’ve played with all the great country artists you could name” says ND Smart, the drummer of the Gram Parsons & The Fallen Angels tour in 1973. “I was the music director of a TV show in Canada called Nashville North for seven years, and we had every top country singer on our show. Gram’s right up there with all of them. If he’d lived, he would have written more records and been an icon.” Barry Tashian, rhythm guitarist on the GP album is not so convinced. “Whether he would have become a worldwide star, I don’t know. You mention the Eagles, but their sound was perfect for the masses. I don’t think Gram would have gone near that. He was too much of a purist…”

FIND THE FULL INTERVIEW FROM UNCUT FEBRUARY 2011/TAKE 189 IN THE ARCHIVE