Earlier this year, speaking to Uncut about her love of Nick Drake, Joan Shelley expressed a preference for “the more intimate recordings, that stripped-downness. When somebody is that good at being the whole band, I want to be as close to the guitar as possible. It has certainly had an influence on my own record making.”

- ORDER NOW: The Beatles are on the cover of the latest issue of Uncut

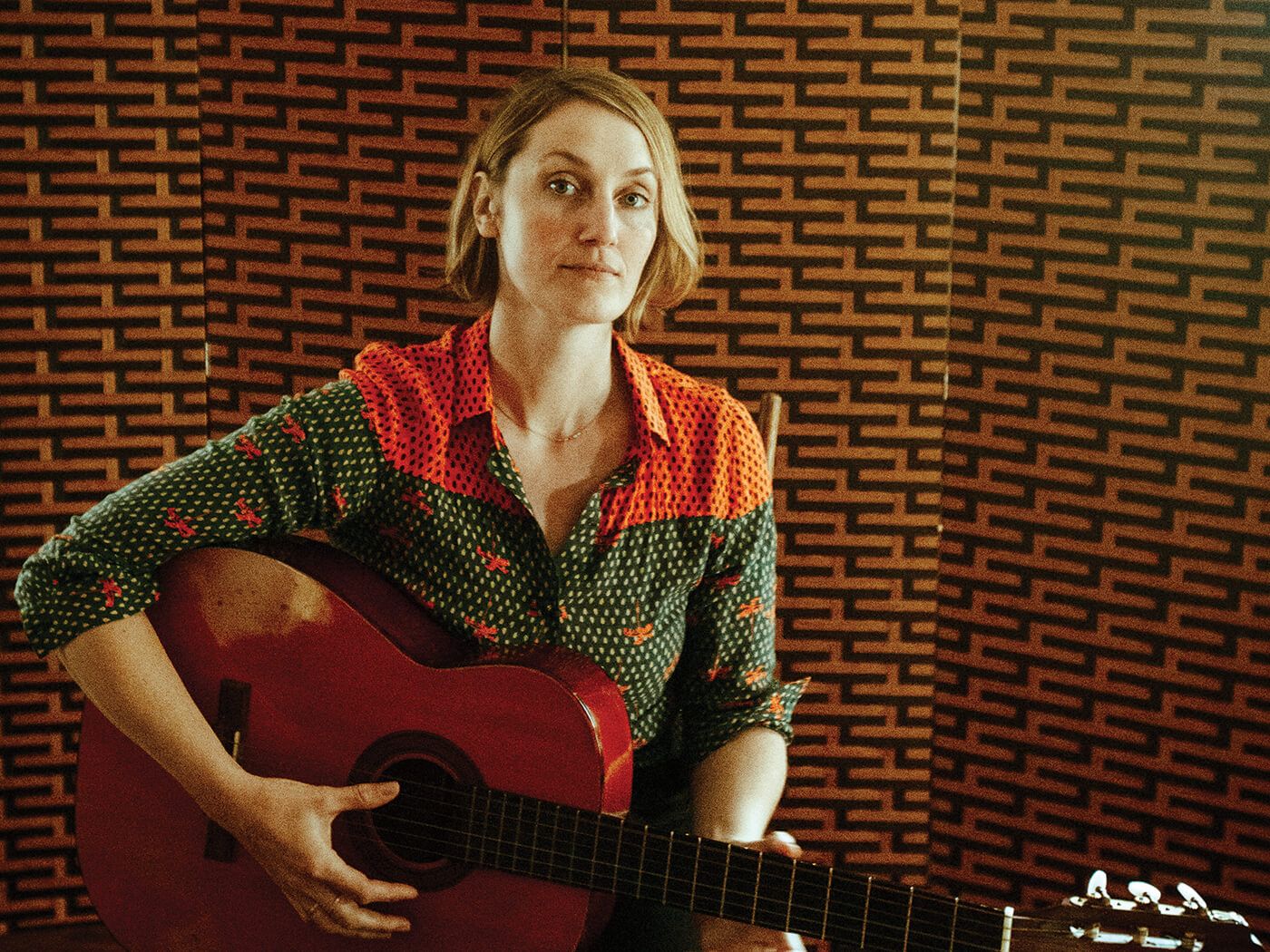

The heart of Shelley’s music since her 2015 breakthrough, Over And Even, is located in the warm, unshowy, close-mic’d interplay between voice and acoustic guitar. So compelling is that sound, any additional textures can feel like minute calibrations, delicate but inessential brushstrokes. Yet like all good minimalists, Shelley recognises the value of the sharp, subversive intervention. Though her music is cool and calm at the centre, a continuous and compelling tension tugs away at the edges.

“I always want there to be a landscape in my music,” Shelley tells Uncut some months later. “It’s not overly done, but I want to be haunted by some weird thing. I think of it as a tiny orchestra, the ghost of Frank Sinatra’s studio band. A little swell.” It’s this shimmering luminosity, this otherness, that makes Shelley the most modern of traditionalists. Without it, her songs would still be beautiful. With it, they become something remarkable.

For her last record, Like The River Loves The Sea, the “swell” was accessed via a trip to Reykjavík to record string orchestrations with local musicians. The augmentations on The Spur spring from closer to home but are no less impactful. The basic tracks for these 12 songs were recorded in Kentucky by Shelley and her musical partner, and now husband, Nathan Salsburg. Further textural flourishes were overdubbed in Chicago, marshalled by producer James Elkington. They include double bass, brass and cello lines, dobro, shape-shifting keyboards and other voices: Meg Baird sings backing vocals on two tracks; Bill Callahan checks in.

The songs were written during a 12-month period which spanned extremes. Shelley went from touring the world to entering lockdown on her “feral” tree farm in Kentucky. Physically disconnected from a community of musical allies, she relied instead on weekly sessions on Zoom with local songwriters; the bulk of these songs were initially shared among that group. Most significantly, she and Salsburg became parents. Their daughter Talya arrived two months after the album was recorded last spring. The event, and the season, signify the hard-won sense of renewal on a record which tracks the “miles beneath our heels” and the tough reckonings which follow, yet finds strength and beauty in the turning of the wheel.

The title track is a hymn to a kind of existential recklessness, to not merely accepting the churn of change but embracing it. “We’ll dance like we’re high/Watch the good times wear out/Come on, ride faster now/Till the old world’s a blur”. Several more songs make a cussed kind of peace with the notion of eternal impermanence. Opener “Forever Blues”, a subdued yet sturdy study in doubt, foregrounds the idea of life as perpetually provisional: “Do I lease you always, is the rent coming due?” Later, on the rollicking “Like The Thunder”, Shelley sings, “You can’t buy it, can’t own it, can’t label it or save it”.

The competing desire for life to change but somehow stay the same runs through an album which swings thrillingly between consolidation and evolution. The lyrics on the flinty title track were co-written with actress Katie Peabody, one of three collaborations with different writers. On “Amberlit Morning”, Bill Callahan not only takes on the role of doleful co-vocalist, a part routinely played previously by Will Oldham, he also contributes lyrics.

The results are mesmerising, an allusive epiphany weaving around a circling guitar motif, delivered at walking pace. Percussive taps and sharp electric guitar licks burnish a lamentation for the instincts we lose to time. “Every child sees it, every child knows”, sings Shelley. “As a child I saw it all”. There are headless geese and cows kept for their milk and skin. Like Seamus Heaney, whose early poetry the song brings to mind, there is nothing soft in Shelley’s songworld. Her depiction of nature is all business – soil, root, rock – while her portrayals of human physicality zone in on chins, bones, spines: the scaffold of a body.

The third co-write is with English novelist Max Porter, author of Grief Is The Thing With Feathers. “Breath For The Boy” leads with Shelley’s insistent piano, its jagged edges softened by recorder and double bass. The strange, haunting beauty of the music aligns perfectly with a darkening study of “poisoned” masculinity.

Switching emphasis from guitar to piano pushes not just Shelley’s writing but the sound and shape of her songs into new territory. “Bolt” is almost anthemic, a stately yet incongruous ballad which swells then ends abruptly, as though slightly abashed by its own grandeur, though not before Salsburg’s gorgeous baritone guitar solo blossoms from the song like a wildflower. “Between Rock & Sky” is a fragment of voice and decaying dots on the keys. Ancient sounding, it lands somewhere between The Unthanks and Karine Polwart, and is the sole moment where Shelley seems to sing directly as the mother she will soon become: “Hear the child arriving/Heaving heart’s first cry”.

Elsewhere, her knack for writing melodies which feel as old and inevitable as time is undiminished. A gorgeous hug of a tune, buffeted with ’60s girl group vocals, “Completely” feels like an instant standard. “Fawn” is equally beguiling, though its folksy simplicity is harnessed to expose the vulnerability of the artist, the lover, the human, portrayed here as a sacrificial offering. “Like The Thunder” is more playful, a merry country-rock spin on Fleetwood Mac’s “That’s Alright”, the unfussy thwack of Spencer Tweedy’s drums driving a warm rush of horns, rolling guitar lines and a sunburst of stacked vocal harmonies. As on “Tell Me Something” from Like The River…, Shelley captures the shake, rattle and roll of carnal longing so well, so cleanly.

“Why Not Live Here” is a simple hymn to the pleasures of staying put, yet the position is fluid. One of the prettiest tracks on the record, “Home” is ambivalent about laying down roots. To leave or return? Shelley can’t be sure. “Stalled in the driveway/The way in or the way out?”

It’s these tensions which raise The Spur to its full height. The magnificent “When The Light Is Dying” was prompted by the memory of listening to the devastating vastness of Leonard Cohen’s final album in the back of a tour van. Yet the grief it depicts is light-footed, unfolding with the sultry classicism of a chanson. The staccato synth strings recall The Blue Nile, slicing through cello and low, lazy horns.

Cohen gets a namecheck – “You want it darker, Leonard sings” – as Shelley once more dances between sorrow and joy, between giving up and keeping on. “Sad is the beginning if the end is all it brings/But still the world keeps turning between the wood, the rocks, the springs”. It stands as a manifesto for an artist determined to give voice to the full sweep of human experience. On The Spur, Shelley captures the ache and the sweetness, the loss and the love, the coming and going of it all, with greater scale and skill than ever before.