Cometh the hour, cometh the man – and if there’s anyone who knows a thing or two about carnage it’s Nick Cave. Some of this he’s historically created himself. Some has been cruelly thrust upon him. But whatever the situation, this is someone who doesn’t shy away from what’s happening; who plays the cards as they fall. Now, locked down like the rest of us (maybe not quite like the rest of us – he makes a couple of mentions of a balcony where he vaults into the imagination and back while reading and notating Flannery O’Connor), he presents something like his own lockdown album.

As anyone who has seen his quote-unquote livestream from Alexandra Palace will tell you, however, there are ways of maintaining normality in lockdown (running, working, “booking a slot”) and then there’s Nick Cave’s way of doing them: interior monologue, swoosh of mane, lingering shot of journal containing “the work”. So it is, in a way, here.

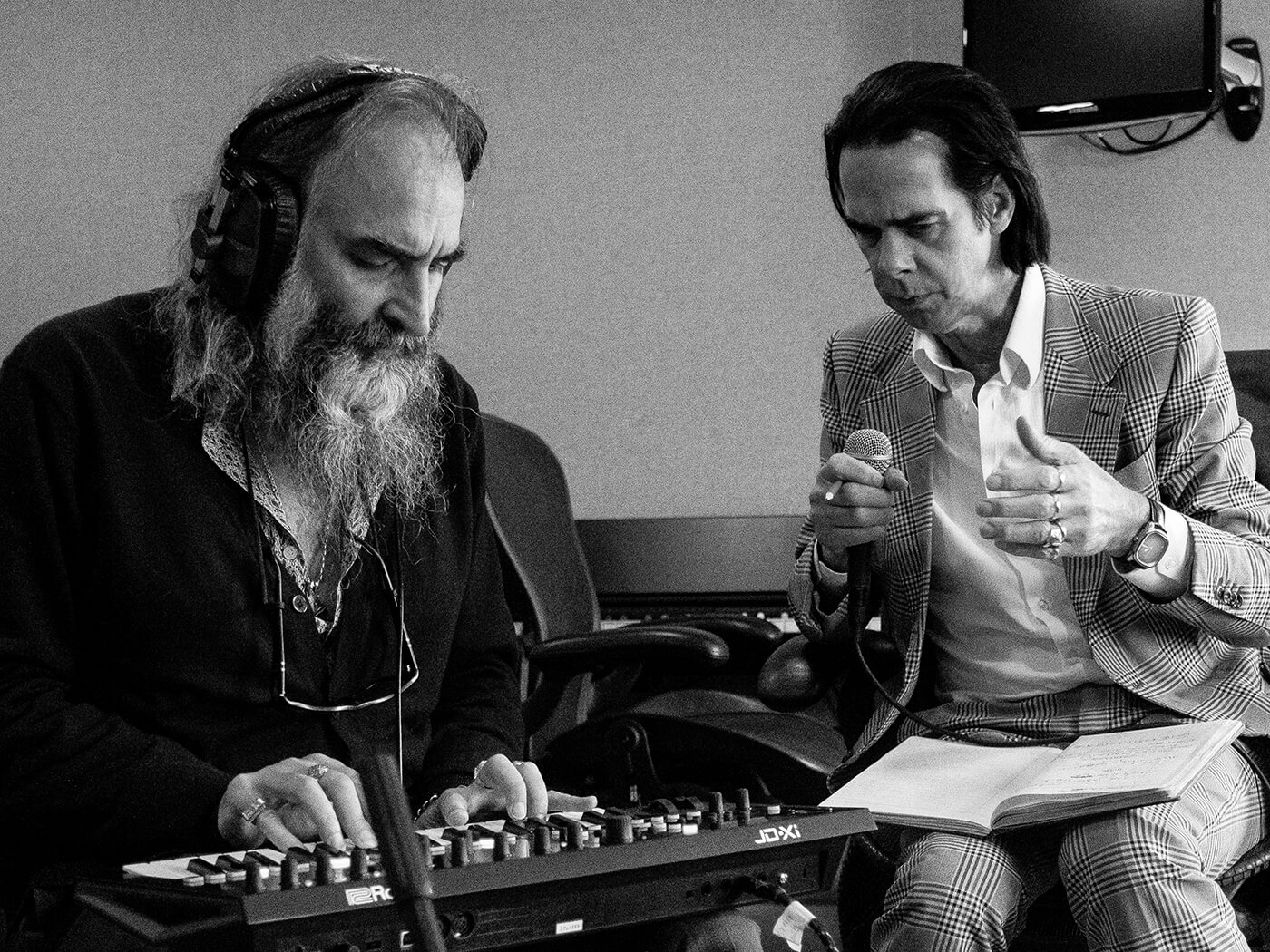

Undoubtedly there are a set of circumstances where this might simply have been Cave and Ellis in some version of a garage, banging out a record. There are hints of it on the great “Old Time”, which finds the duo as the doctoral thesis version of Alan Vega and Martin Rev, on a Lynchian road trip, complete with dive-bombing synths and things with horns in the bushes. In his Red Hand Files, Cave has mentioned his disappointment at the postponement of touring plans and how he misses the “recklessness” of The Bad Seeds, and here “Albuquerque” wistfully evokes stasis, while “Carnage” itself suggests if we’re going anywhere anytime soon, it will be a journey in our imagination.

In the meantime, Cave and Ellis employ their own recklessness. The album appears as if it is going to begin in a familiar ballad mode before the mix sucks the piano and violin down into the depths of some sophisticated techno club. Opener “Hand Of God” becomes an extraordinary Bond theme of the mind. It’s Grinderman does Portishead, and Cave is swimming in the deepest part of creativity’s river, at the mercy of its current: “Let the river cast its spell on me…” As the chorus builds to include more voices, it’s tempting to think that this might be some kind of video-conferenced contrivance, families and neighbours lending their voices to a lo-fi project.

As ever, though, there’s slightly more going on behind the scenes. This might not be a Bad Seeds album (although drummer Thomas Wydler is on there), but nor is it one of Cave and Ellis’s minimal excursions into the film soundtrack wilderness. Recorded between late November 2020 and January 2021, there’s a proper team on board here. The two highly accomplished multi-instrumentalists themselves, of course. Then there’s a five-piece choir and a string section.

The world provides the rest. Compared with the highly structured Ghosteen (a double album meditation on grief and spirituality, complete with intermission), Carnage is a more concise though no less ordered record. Much as the Bad Seeds’ songs now push into oceanic drift, Cave’s narratives move between worlds fictional and not, the horrific and the consoling. In “White Elephant” he references the Black Lives Matter protests, specifically the Bristol ones, and builds a cumulative image of a boiling world hatred, a suspicious and violent conservatism: “I’ll shoot you in the fucking face/If you think of coming around here”. It’s a piece so toxic that at the end it needs its own hymn of hope to try to heal it in the last few minutes. You’ll find this somewhere between Primal Scream’s “Movin’ On Up” and “All You Need Is Love”, beaming a positive message to the world.

In the beautifully arranged “Lavender Fields”, meanwhile, Cave ponders his own blessed, lavender-tinged place in the creative world (sidebar: some believe Christ to have been anointed with lavender oil), where he now finds himself travelling a “singular road” and doing so “appallingly alone”. Once he was “running with my friends/All of them busy with their pens”. Now (is he perhaps thinking of his ’80s contemporaries Mark E Smith and Shane MacGowan?) he finds himself in a field of one – as others have fallen away, or behind, while he continues the journey. At the end of the song, the “hymn” lyrics are repurposed in a calming Spiritualized-like coda. “Shattered Ground” is terrifying: imagining the singer literally in pieces, atomised at the end of a relationship, while “Balcony Man” finds the singer flirting with sanity but ultimately consoled by the beauty of the morning and the world.

If nothing else, there is a particular type of business that has thrived in these times – pivoting to online, “making lemonade” from the vile ingredients the world has lately been served. Nick Cave is far too human and empathetic a musician to respond by using them as a pretext for a change of gear into pure experimentation. Instead, he has met them honourably with a great record on its own terms: recognisably himself, aspiring to rise above, much like the rest of us, doing the best he can.