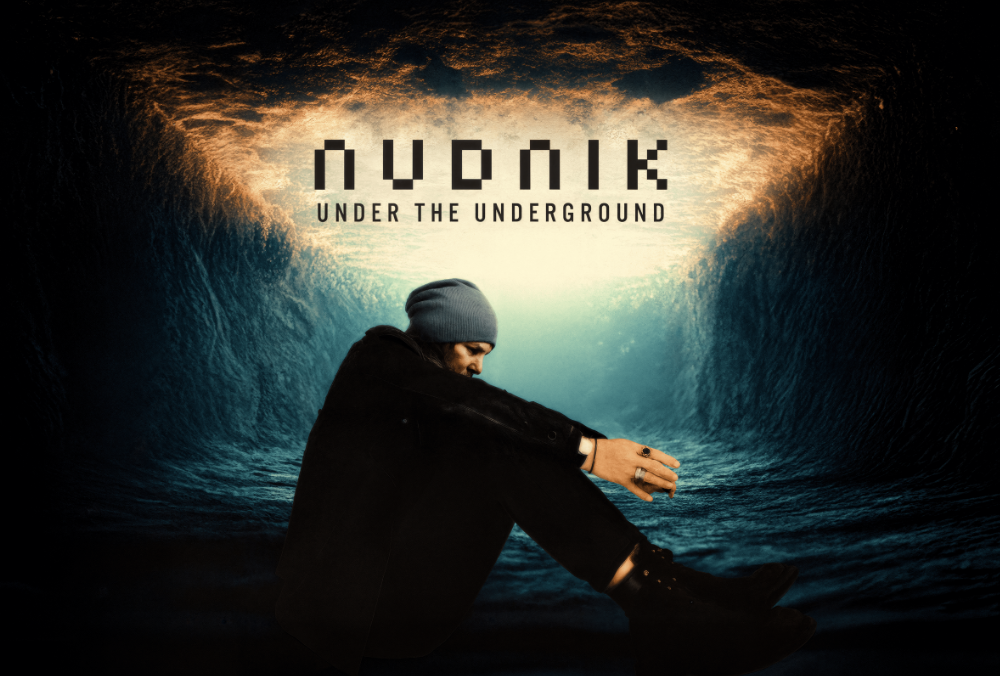

Known for turning inward and exploring the quiet spaces of the mind, NUDNIK has returned with Under the Underground, a record that’s intimate, precise, and profoundly human. The album isn’t about spectacle or immediacy—it’s about presence, reflection, and letting emotion breathe.

Since the release of his debut album iNODE, NUDNIK has been navigating personal loss, life changes, and creative evolution. These experiences shape every note of Under the Underground, giving the music a raw honesty without feeling confessional. Minimalist but deliberate, the record balances tension and calm, silence and sound, creating a listening experience that feels both private and expansive.

With this album, NUDNIK is sharing a space where doubt, curiosity, and self-awareness collide, inviting listeners to move through it at their own pace. We sat down with him to discuss the journey behind Under the Underground, the role of grief in creativity, and how music can be both therapy and conversation.

Your new album is called Under The Underground. What does that title mean to you, and how does it represent the themes of the record?

The title came out of thin air. It was actually my first post on Facebook after the release of my debut album iNODE. At the time, it simply described how I felt — new, unknown, and existing beneath whatever “the underground” was supposed to be. The phrase stuck. As the album took shape, the meaning deepened. Shortly after recording began, my father passed away, and my mother became ill. Under The Underground started to feel like a metaphor for death and burial, but also for something more abstract — a space beyond what we can fully understand or explain. Since then, the title has taken on another layer for me. It represents a place you live for a while — emotionally, creatively, or spiritually — until you decide you’re ready to surface and change. In that way, the album isn’t just about loss, but about what happens in the quiet, unseen space before transformation.

Under Under The Underground moves through the stages of grief with striking intention. When you were writing it, did you recognize those stages as you were living them, or did that structure only reveal itself in hindsight?

First and foremost, making the album was therapy for me. It was how I coped with loss and with a lot of sudden change in my life. I was very aware that I was moving through different stages of grief as I was writing and recording. I could feel those emotions clearly, and I leaned into them rather than trying to avoid them. Certain songs naturally aligned with specific feelings — anger, confusion, acceptance — and some tracks were emotionally harder to work on than others. As a whole, though, the process was deeply cathartic. The album became a place where I could sit with those emotions honestly and let them exist without trying to resolve them too quickly.

Your earlier work began in experimental synth spaces before evolving into guitar-driven songwriting. What did the guitar allow you to express emotionally that electronics alone couldn’t?

The guitar — and bass guitar as well — have been with me for a long time, and they naturally carry a more human, physical feel than a synth alone. There’s something about the imperfections, the touch, and the way dynamics shift in real time that makes emotional expression feel more immediate. That said, even when I work with synths, I don’t approach them in a purely programmed way. I almost always perform the parts live rather than penciling in MIDI, even if the part itself is very simple. The only real exception would be sequenced synth patterns, which serve a different purpose. Because I don’t play drums, those parts are programmed, but with a lot of care and intention. I’m always thinking about feel — how a human might naturally push or pull a rhythm — and trying to preserve that throughout the record. Ultimately, the guitar just gave me another way to make the emotions feel lived-in rather than constructed.

Your music often feels like a conversation with the self, unfiltered and sometimes uncomfortable. Do you view songwriting as documentation, therapy, or confrontation?

I see songwriting as a way of investigating an idea — sometimes emotional, sometimes more cerebral. Writing a song takes that idea to another level of meaning, and there’s always a point in the process where it becomes what it’s going to be, almost outside of your control. At that stage, the song just has to be what it is. I don’t necessarily see it as a conversation with myself, though I’ve certainly been known to do that. I think of it more as a conversation with the listener — or at least an attempt at one. I’m letting them know what’s going on with me in an honest way, and maybe, in doing so, offering a perspective that helps them approach something in their own life a little differently.

As Robert Marc Lieblein and as NUDNIK, where do those identities converge, and where do they deliberately remain separate?

Yes — sorry to disappoint you, but Mr. NUDNIK is Robert. I understand the idea of persona, and I’m not opposed to it. I’m willing to change one, but only if I can actually live it. In a strange way, saying I’m not a persona probably becomes the persona — and I’m okay with that. My full heart is in the NUDNIK music. Robert doesn’t really have much of a life outside of it at the moment, and I say that sincerely, but also with a bit of humor. This is where my energy goes, where I think, where I work things out. I’m not stepping outside myself to make the work — I’m stepping fully into it. If there’s a distinction at all, it’s practical rather than emotional. NUDNIK is the space where everything gets expressed. Robert is the guy who keeps the lights on so that space can exist.

“Zen Silence” reads like an instruction manual for a panic attack. Were you writing that for the audience, or were you trying to talk yourself off a ledge?

Both, really. I was writing it for myself, but also for anyone listening. It’s an attempt to urge resilience — to slow down, to let go, to stay present when things feel overwhelming. There is a panic attack inside the song, but it’s paired with an answer. The instruction is simple, even if it’s hard to follow in practice: pause and keep calm. Zen Silence is about trying to interrupt that spiral before it fully takes over. The uncontrollable panic comes later, in Every Second Counts. That song lives inside the moment when those tools stop working. In that sense, Zen Silence is the attempt to steady yourself before the ground really starts moving.

Can you tell us a bit about how “Blue Day” was written?

Blue Day first came to me during a walk at night. I knew I wanted to write something that quietly paid homage to David Bowie, and the word “blue” felt like the right impulse to begin with. While walking, I sang a rough melody into my phone — the phrase was “Blue God Day” at first. That melody stayed, but the “God” part didn’t feel right to me, so I let it go. What remained was the feeling behind the word blue. It can mean a beautiful blue sky, or it can mean sadness, and I liked that emotional ambiguity. It was the first song I wrote and recorded for the album, and even with the sadness in it, the song was about choosing how to respond to the day you’re given.

You’ve mentioned that “Blue Day” is a nod to David Bowie. Which of his eras or songs inspired you the most when working on this track?

There are a few very direct nods in there. I actually play a bit of Space Oddity within the song, so that connection is literal. Lyrically, the word “blue” also comes from Bowie’s line, “Blue, blue, electric blue, that’s the color of my room,” which always stayed with me. If I had to name one primary influence, though, it would be Low. That album’s emotional restraint and atmosphere were a big reference point. I even experimented with some recording techniques Tony Visconti used during those sessions — especially the echoing vocal moments. The repeated “blue” at the end of the song was directly inspired by that approach.

For those who are new to your music, how did the NUDNIK project originally start back in 2015, and how has it evolved into what we hear today?

The ideas behind NUDNIK actually began before 2015, but they didn’t fully come together until much later. The project first felt complete with the release of iNODE in early 2025, which was the point where everything I had been circling for years finally crystallized into a cohesive body of work. Under The Underground represents a clear progression from there — not just in production quality, but in vulnerability. I became more willing to let the emotional core of the work come through without protecting it or overthinking it. The songs are more present, more honest, and less concerned with resolution. What you’re hearing today is simply where I am right now. And if the project continues, it will keep moving in the same direction — me doing my best to examine the ideas that surface in my head and working through them musically, without shortcuts or disguises.