“Do you remember the Harlem Cultural Festival?” the interviewer asks, and 50 years on,

by the distant looks on some faces, you sense even people who were there are still not sure if it was all some hazy, childhood ’60s summer dream. After all, until recently it had left barely a ripple in the wider culture, overshadowed by Woodstock happening a couple of hundred miles north and the ongoing political turmoil of 1969.

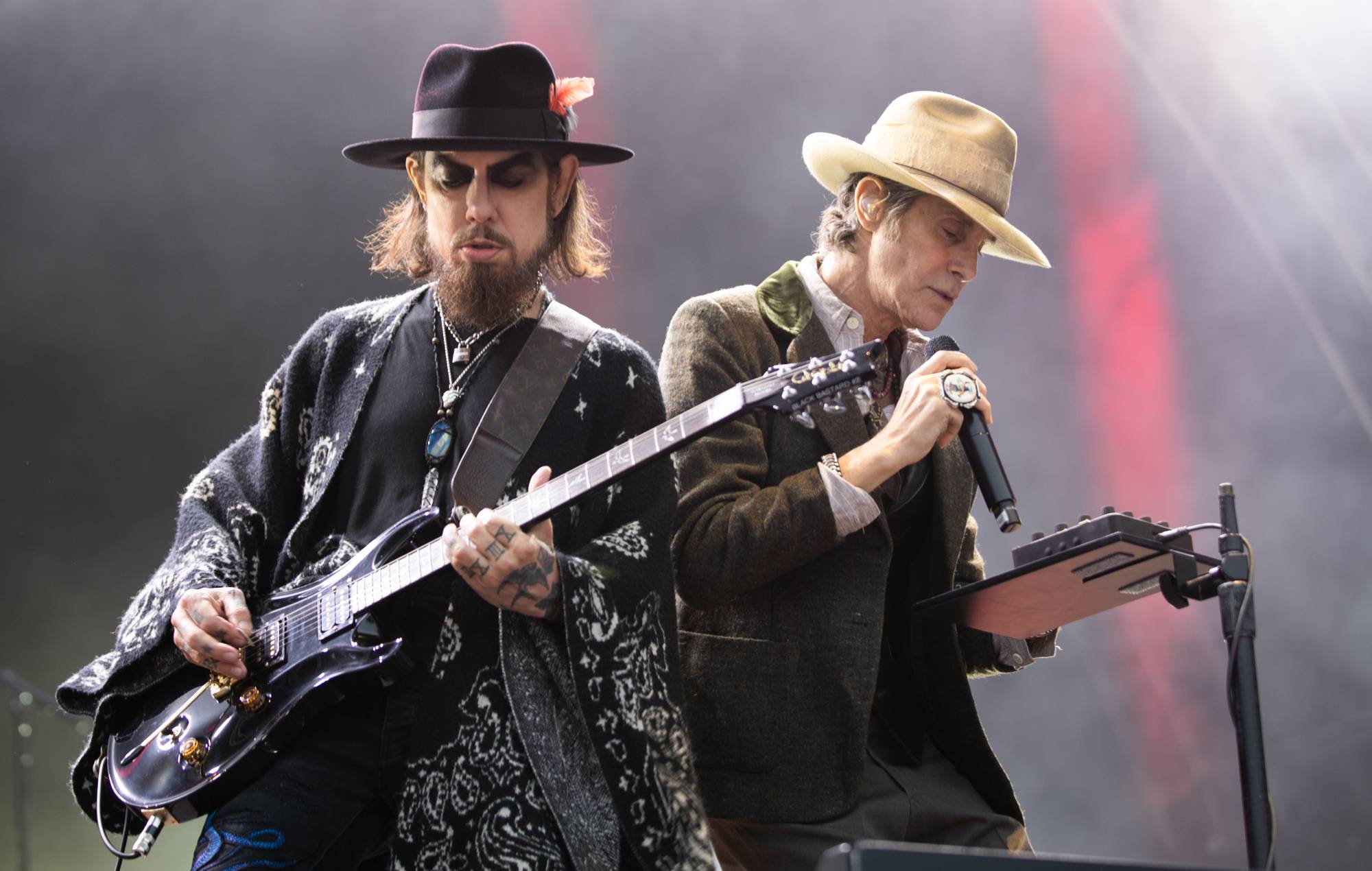

- ORDER NOW: Nick Cave is on the cover of the October 2021 issue of Uncut

“The Harlem Cultural Festival was, indeed, a meaningful entity,” the journalist Raymond Robinson wrote at the time, “but was it fully appreciated? The only time the white press concerns itself with the black community is during a riot or major disturbance…” Sure enough the tapes of these six incredible free shows that took place in Mount Morris Park through June, July and August of 1969 have languished in a Westchester basement for more than 50 years.

What’s brought to light in Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s thrilling and timely doc, is a revelation: an event that rewrites everything you thought you knew about postwar pop. Here in a park on 124th Street, as Apollo 11 landed on the moon and the Panther 21 Trial rolled on, as the long mourning of MLK continued and the heroin epidemic burgeoned, more than 300,000 gathered to witness a stunning staging of the Black American musical diaspora: from blues to jazz to soul, Motown and Sly Stone’s psychedelic fantasia.

But in one sense the music is secondary. Witnesses agree they’d never seen so many black people together before. The event was put together by eccentric, enigmatic lounge singer turned cultural hustler Tony Lawrence, under the patronage of Republican mayor John Lindsay and with the sponsorship of Maxwell House. The police were largely absent, with the Panthers providing security. The crowd is wonderful: grooving old guys in trilbies, jiving matriarchs, dapper dudes in dashikis. “When I looked into the crowd I was overtaken with joy,” says Mavis Staples, still moved 50 years later.

The music is, of course astonishing. Stevie Wonder, still only 19 but greeted as a conquering hero, spiffed up in a gold cravat, like some regency dandy, casually playing the most incendiary drum solo you’ve heard, while a courtier holds a brolly above him. Nina Simone, a visiting dignitary from cosmic Wakanda, firmly but politely asking whether we’re willing to smash “white things”. Sly And The Family Stone, and their white drummer Greg Errico in particular, slowly winning over the crowd before blowing their minds with an irresistible Higher. And then there’s Mavis Staples, humbly accepting the gospel torch from Sister Mahalia Jackson, as they’re driven to inspired glossolalia in memory of Martin Luther King…

And what about David Ruffin, a snazzy, lanky crow, leading the crowd with an unearthly falsetto on My Girl, and Gladys Knight burning up I Heard It Through the Grapevine? Maybe the weirdest triumph of all are the 5th Dimension, dolled out in creamsicle orange and Big Bird Yellow, surely the whitest sounding group of 1969, dazzling the crowd with Let the Sunshine In.

“We were creating a new world,” one woman remembers thinking, “Harlem was our Camelot.” With Summer Of Soul, that myth feels close enough to touch.