Here's a comparison you probably never thought you'd hear: child actor turned Riverdale lead, Cole Sprouse, is getting mistaken for none other than Empire star Terrence Howard in a new photo shoot. On Wednesday (May 20th), Cole posted some photos from the summery shoot taken by photographer Alex Hainer, in which the actor rocks his natural blonde hair colour, a moustache and goatee, and a rare tan. "Some more from @alex_hainer to sever my audience in twain," Cole wrote in the caption on Instagram.

The photos began circulating online, and it didn't take long for someone to point out that Cole low key looks a lot like a rather unexpected person: Terrence Howard.

The two began trending together on Twitter, which confused a ton of unknowing people at first.

Christina Milian’s BF Matt Pokora Accused Of Making Racist Hair Comparison

Christina Milian’s boyfriend Matt Pokora was under fire after seemingly comparing her daughter’s hairstyle to the microbe emoji.

Christina Milian’s boyfriend, Matt Pokora, faced some heavy backlash for seemingly comparing her daughter Violet’s hairstyle to the microbe emoji, many calling the joke racist. On Thursday, Matt, who is also the father of Christina’s second child, Isaiah, posted a video of 10-year-old Violet on his Instagram story. In the clip, Matt filmed Violet while she had her hair up in Bantu knots, as she asked him “what are you doing?” When he posted the video, he added a microbe emoji in the caption, along with a laughing emoji and a heart emoji. He even felt the need to draw an arrow from the microbe pointing at Violet’s hairstyle, seemingly implying that her hairstyle bears a resemblance to the symbol.

Many folks were outraged by the comparison, especially since the microbe emoji has come to be used across the Internet to represent the coronavirus. The implication that her hair “looks” like or even “is” a virus or disease was offensive to some people, especially since Matt is a white man mocking a young black girl’s hairstyle.

Matt later took to his IG stories again to shared some videos of himself and Violet to prove how close they are. The french musician posted a clip of Violet heading off to school with the caption, “Self confidence on point.” In the video, he tells Violet to “have a great day, be great, you’re a winner.” He shared some more videos of a similar nature, demonstrating how supportive he is of his honorary step-daughter. He has yet to directly address the microbe-hair-comparison controversy

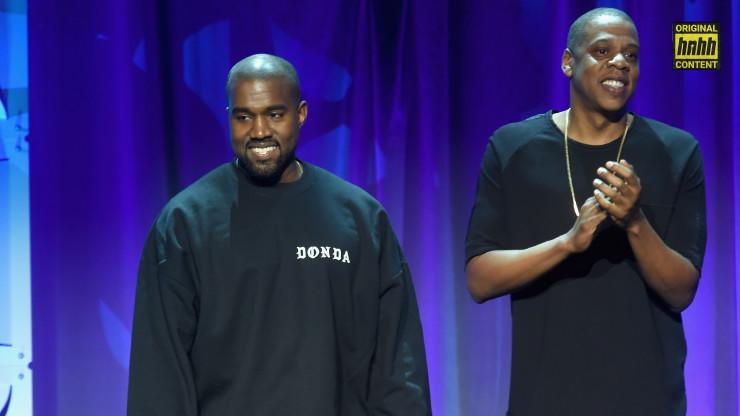

Kanye West Vs. Jay-Z: Who Had The Better Sophomore Album?

Jay-Z and Kanye West go head to head in the latest installment of “Who Had The Best Sophomore Album?”

Kanye West is undoubtedly one of the most critically acclaimed musicians of the 21st century. But it’s not only his musical career that’s been entertaining to follow. From famously interrupting and ruining Taylor Swift’s 2009 MTV Video Music Awards acceptance speech because he believed Beyonce had been snubbed, to claiming that his utterly strange support of Donald Trump was “God’s practical joke on all liberals,” the Chicagoan has cultivated a public persona of being brash, arrogant and bizarre. But let’s face it, the man’s a born entertainer and this audacity absolutely spills into his music. Since 2004, when he strode into the rap scene with his first project, College Dropout, it’s been mostly back-to-back hits. To avoid a sophomore slump, though, Kanye knew he had to build off the foundation he laid on his debut. Which is exactly what he did in 2005 with his exquisite follow up album, Late Registration.

Call him what you will — Hov, Jigga, or simply Jay-Z — we’re talking about one of the most influential voices in the world today. Jay-Z’s gimlet-eyed focus has turned him into the quintessential black capitalist, an entertainment business mogul with a career pathway strewn with Grammy awards, advertising sponsorships, record labels, and philanthropic endeavors. In 2019, he was named by Forbes magazine as the first hip-hop artist billionaire, thanks to investments in clothing, champagne, cognac, the ride-hailing service Uber and his Roc Nation entertainment company. But none of this would have been possible without his music. Born Shawn Carter, he grew up in Brooklyn’s tough Marcy Houses projects and broke onto the scene with his 1996 debut album, Reasonable Doubt. His profound talent as a lyrical marksman was immediately apparent as was his commitment to tell the stories of black men trapped, and too often killed, by the cruel system in which he was raised. But after national success with his debut, could he prove himself on the worldwide stage with his 1997 sophomore album, In My Lifetime, Vol. 1.?

Daniel Boczarski/Getty Images

LYRICISM

Jay-Z’s sophomore project In My Lifetime, Vol. 1 helped solidify his reputation as a true wordsmith. Showcasing his uncanny storytelling abilities he effortlessly raps about his rapid upward trajectory, the conflicting emotions of sudden stardom, and becoming the hottest new artist in Brooklyn. On the first track, “Intro/A Million and One Questions/ Rhyme No More,” he dives right into calling out the doubters and detractors:

“A lot of speculation

On the monies I’ve made, honies I’ve slayed

How is he for real? Is that N***a really paid?

Hustlers I’ve met, dealt with direct

Is it true he stayed in beef and slept with a TEC?

What’s the position you hold?

Can you really match a triple platinum artist buck by buck

But only a single goin’ gold.”

Never mind that Reasonable Doubt, Jay-Z’s debut album, only achieved modest success on the charts and sold less than 500,000 copies in the first year — it doesn’t stop him from bragging openly about his newfound riches: “Can you really match a triple platinum artist buck by buck/ but only a single goin’ gold.” He even audaciously compares himself to the then King of New York, Notorious B.I.G., who had only recently been murdered. Reminding everyone of his “triple platinum artist” status, Jay-Z wastes no time swooping in to claim the title for himself.

While his debut was all about exposing his mafioso style and bad boy mentality, by contrast In My Lifetime is an up-close-and-deeply personal story that showcases Jay’s talent for mining the emotional landscape. In “You Must Love Me” he opens with a verse to his addict mother, who was struggling with her own demons when her son began selling drugs: “All you did was motivate me: ‘Don’t let ’em hold you back!’/What’d I do?/Turned around, and I sold you crack.” It’s a harrowing account of a miserable childhood of violence, drugs, and a sadly marginalized life. Through it, he continues to rap, “You must love me,” which rings out like a sombre and beautiful echo. On another track, “Imaginary Player,” he appears eager to show his young followers that business acumen and rap can coexist:

“You got show dough, little to no dough

Sell a bunch of records and you still owe dough

I got 900 and 96 plus 4 mo’ dough”

Jay’s distrust of record companies was well documented even early on, leading him to form his own lucrative label with Dame Dash in Roc-A-Fella Records. In the clever bar above, he warns artists who are languishing in dead-end record labels, making money only from performances and not from album sales. In many ways, In My Lifetime served as one of the first manifestos on how to break free of the shackles of poverty and achieve success. And when it’s narrated by one of the greatest storytellers in rap history, you listen.

Regarded as one of the finest hip-hop albums of the century, Kanye’s sophomore work Late Registration also touches on thorny subjects such as poverty, drug trafficking, racism, the toxic college fraternity culture and the blood-diamond trade. By doing so, Kanye proved, especially in 2005, that he was one of the only mainstream rappers willing to tackle political issues. In “Diamonds,” he raps about the links between the jewellery trade and Sierra Leone’s civil war. In “Crack Music,” he exposes the oppression of black militancy by drug use, while in “Roses,” he takes on America’s healthcare crisis. Not a natural storyteller, Kanye’s lyrics show flashes of brilliance occasionally. But no one can ever accuse him of not using his platform to shine a spotlight on controversial topics — which is more than you can say about his peers.

Late Registration is peppered with skits and acapella monologues to relay various tales, including one about Kanye joining a black fraternity, where a proletarian ethos rules: no need for fancy cars or trophy girlfriends. However Kanye is expelled from the fraternity after getting caught breaking the rules: making beats for money, taking showers, and buying new clothes. It’s Kayne’s attempt to debunk the myth that the American dream is attained only through materialism. “Gold Digger” is unquestionably the best-known song on the album. Featuring the sensational voice of Jamie Foxx, Kanye delves into a narrative about the dire life of an African American man being financially manipulated by his wife, a.k.a. the gold digger.

“I know there’s dudes ballin’, and yeah, that’s nice

And they gonna keep callin’ and tryin’, but you stay right, girl

And when you get on, he’ll leave yo’ ass for a while girl”

Then comes a superb plot-twist: after being faithful and sticking with his wife through all their trials and tribulations, the husband betrays her with a white woman. The gold digger needs a rich man, the rich man needs a trophy wife. It’s life in hip-hop ville, according to Kanye. “Addiction” is an underrated gem on the album, and in it, Kanye explores the existential dilemma of finding satisfaction through life’s vices:

“What’s your addiction? Is it money? Is it girls? Is it weed?

I’ve been afflicted by not one, not two, but all three”

He continues:

“Why everything that’s supposed to be bad make me feel so good?

Everything they told me not to is exactly what I would

Man, I tried to stop man, I tried the best I could

But you make me smile”

Kanye’s music is his conduit to relay stories about his life, his addictions and his obsessions. And Late Registration is full of relatable stories. He may well be a better producer than a rapper, never having delivered anything as lyrically intricate or smooth as our man Jay. But Ye, even back in the 2000s, was savvy enough — and you can’t deny his passion and determination — to know that storytelling brings people together.

Michael Buckner/Getty Images

PRODUCTION

Kanye’s production skills are second to none. Late Registration is proof of his talent. The early 2000s saw work from many memorable producers but Kanye was one of the first to use samples and orchestral melodies behind his drums to provide upbeat and soulful tempos. Aside from Dr. Dre and Scott Storch, he was one of the earliest to introduce the piano to the genre, which has since become one of the most used instruments in hip-hop. It’s often said that Kanye is one of the best producer-songwriters in music history and this album was probably where that legacy first took root.

In My Lifetime showcases textbook, New York-style beats from the late 90s. Puff Daddy’s production team, The Hitmen, handled this album and included beat masters such as DJ Premier, Ski, Buckwild and Prestige. With the expertise of this top-tier production ensemble, the album possessed a vastly more polished sound than its predecessor. It even featured a series of cleverly placed samples that included Biggie Smalls on “Face Off” and Benjamin Lattimore on the intro track. In retrospect, it’s clear that this was the pivotal moment when Jay-Z began honing his musical techniques and decided to transition from using standard drum beats to more sophisticated ones.

Kevin Winter/Getty Images

IMPACT

In My Lifetime Vol. 1 and Late Registration are undoubtedly two of the most prominent hip-hop albums in the past thirty years. For Jay-Z, it was his first opportunity to start a global dialogue about his impoverished beginnings, paired nicely with some bragging about his jiggy and newfound lavish lifestyle. But at its core, it was an album that spoke to the streets and all of the young people living there who endure so much. Go ahead, dream, Jay-Z tells them, because you too can straddle both extremes.

For Kanye West, Late Registration was proof of his brilliance and his role on this earth: to transform the production-scape of rap albums forevermore. People also learned that he’s an artist willing to start necessary dialogues by going to places many rappers are too afraid to deal with. The world got their first taste of the full Kanye West package with Late Registration, hailed an “undeniable triumph” by Rolling Stone magazine and adored by millions. Let us know which album you think is best.

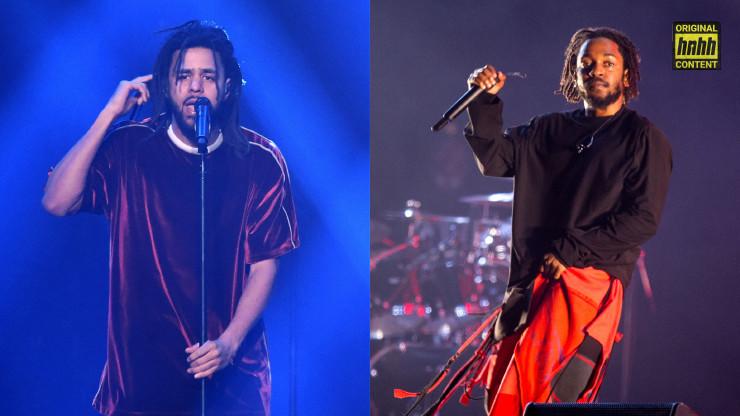

Kendrick Lamar Vs. J. Cole: Who Had The Better Sophomore Album?

Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole go head-to-head.

“Genius.” It’s a term that gets thrown around in think-pieces across the internet every time one of these two guys drops new music. For Kendrick, the cachet was earned from the beginning after his major-label debut, good kid, m.A.A.d city. With tracks like “The Art of Peer Pressure,” and “Sing About Me, I’m Dying Of Thirst,” Kendrick displayed an indisputable knack for storytelling, combined with a distinct ability to carry overarching narratives throughout an album. Cannodading beats such as that on “m.A.A.d. city” juxtaposed with the drowsy, intoxicating production of “Swimming Pools” showed K-Dot knew when to turn it up and when to take a nuanced approach.

J. Cole attained the distinction in a slower fashion. Over the course of several solid mixtapes, Cole gained hype as one of the most promising young talents in the game, a reputation he would cement in the mainstream with his debut, Cole World: The Sideline Story. Cole proved he knew introspection with songs like “Lost Ones,” but could also drop hits such as “Work Out,” or “Lights Please.” His love for Jazz shines through on production throughout the album that feels anachronistic of the ’90s. Slow it down, add in some piano, and Cole has a baby-making-beat like “In The Morning” or “Lights Please” ready to go.

By Born Sinner and To Pimp A Butterfly, Cole and Kendrick found themselves in similar predicaments: Both artists had proved they could make a hit, but could they, not only do it again, but fight off a sophomore slump and improve their game?

Taylor Hill/Getty Images

LYRICISM

“It’s way darker this time,” Cole warns to start Born Sinner‘s harder-hitting intro “Villuminati.” It’s one of the conceptually tighter tracks on the album. Cole struggles between staying true to himself and being “real like Pac,” or flaunting his newfound fame and bragging “like Hov.”

Sometimes I brag like Hov, sometimes I’m real like Pac

Sometimes I focus on the flow to show the skills I got

Sometimes I focus on the dough, look at these bills I got

Throughout the album, Cole loosely follows the troubles of fame and fakeness of Hollywood, but at times tangentially tackles other topics that distract from an overarching purpose. “Power Trip,” for instance, is a smarter, more focused update to Cole’s aforementioned “Lights Please” and “In The Morning.” Cole presents the negatives of desire, playing a version of himself so infatuated with his crush he turns to murder (at least in the music video). He uses alcohol to battle his obsession and despite his rising fame, he can’t get over this girl. It’s an easy highlight from the album– the only issue being that it fails to contribute on a grander scale in any meaningful way.

The highest point on the album comes 15 tracks in with “Let Nas Down.” The lyrics detail the story of Nas, Cole’s idol, hearing his track “Work Out” and being disappointed in the radio-friendly style. Thematically, this is the most moving presentation of Cole’s struggle with fame. He explains the pressures of needing a radio-friendly single for labels to have faith in an artists’ commercial value and how the pressure forces artists to sell out.

By my mind that kept on sayin’

“Where’s the hits?” You ain’t got none

You know Jay’ll never put your album out without none

And, dog, you know how come

Labels are archaic, formulaic with they outcome

Overall, Born Sinner possesses a number of solid hits from Cole, with the occasional impressive witticism, but when presented as a complete package, it’s tied together like a poorly wrapped gift on Christmas.

With To Pimp A Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar takes his pen-game to unparalleled levels. Rare is the album as perfectly written as TPAB. On “Wesley’s Theory,” Kendrick opens the album with a sample from Boris Gardiner’s “Every N****r Is a Star,” and an introduction from Josef Leimberg. Both are callbacks to the album title and present imagery of a caterpillar emerging from a cocoon to become a beautiful butterfly; a clear metaphor to Kendrick rising from Compton into fame. Immediately the vibe is cut as Kendrick raps from the present. He paints rap as a woman whom he once loved but now merely fucks to “get my nut.”

From here on out, Kendrick tackles a new societal issue on each track: “Institutionalized” handles institutional racism; “u” handles depression; “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” handles beauty standards; and so on. Many tracks end with a new line from a mysterious poem. The songs all seem ostensibly unconnected, as if To Pimp A Butterfly is a series of anthologies, until a full poem is revealed at the end that ties everything together.

Lyrically, “These Walls” is a highlight from the album and an easy way to compare Kendrick’s style on TPAB to Cole’s on Born Sinner. For Kendrick’s sensual track, as opposed to Cole’s “Power Trip,” Kendrick tells the story of sleeping with the girlfriend of a man who is in jail for murdering Kendrick’s friend. Throughout, he continuously juxtaposes the walls of the woman’s vagina to the walls of the prison.

These walls want to cry tears

These walls happier when I’m here

These walls never could hold up

Every time I come around, demolition might crush

While Kendrick ran out of steam by the end of good kid with forgettable tracks like “Real” or “Compton,” he proved he doesn’t plan on quitting early this time around by finishing strong with some of his best tracks to date in “The Blacker The Berry” and “i.” “Mortal Man” concludes the album by revealing a conversation between Tupac and Kendrick using audio clips from an interview with Tupac prior to his death.

PRODUCTION

Production is Cole’s strongest asset on Born Sinner. It consistently stays true to his “darker” promise throughout. Cole produced the vast majority of the project himself, an impressive feat that helped give Born Sinner much-needed congruency. Each song is hard-hitting, beautiful, or both, with a number of beats including a spiritual feel that retains the religious tone of the artwork. Even the first sound on “Villuminati” stems from a choir. “Trouble” is the best example of this. It’s the darkest song on the album, but the lyrics are contrasted, in addition to the trap drums, with a chorus sung by a choir.

Cole implements sampling in a number of successful ways throughout Born Sinner such as on the track “LAnd of the Snakes,” which incorporates the classic Outkast song “Da Art of Storytellin’ (Pt. 1).” The sample subtextually compares Cole’s track to Outkast’s, as both speakers reminisce about girls from their past.

To Pimp A Butterfly forfeits any popular rap tropes from the time, instead favoring an amalgamation of Jazz, Funk, Soul, subtle 90’s boom-bap, and more. The production on every track is remarkably catchy and consistently matches the overall tone of the song and album as a whole. Kendrick tapped a myriad of talented musicians to help him in this regard: Flying Lotus, George Clinton, Sounwave, Pharrell Williams, Thundercat, Dr. Dre, Boi 1da, and more all assisted in producing this masterpiece.

“The Blacker The Berry” is the most boisterous track on TPAB. The beat aligns with the sheer anger Kendrick throws into the lyrics. He tackles self-hatred, black on black crime and more while the beat comes alive to rage as loud as Kendrick himself, before imploding into a soft, sultry jazz tune to conclude the record. Skip back five tracks and you’ll find the most euphoric production on the project. “For Sale? (Interlude)” sees Kendrick rapping in the third person from the perspective of “Lucy,” short for Lucifer, who represents major labels — not to mention the devil. The beat is piano and synth-heavy and presents an eerie disposition with the lyrics.

IMPACT

Both Born Sinner and To Pimp A Butterfly are important albums in the discographies of J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar. For Cole, Born Sinner showed that he could return to a more conscious and lyrical style of rap that helped him rise to fame through his mixtape era. Radio-hits like “Work Out,” as he explains on “Let Nas Down,” caused him to lose faith and reexamine his artistic merit. Cole was able to come back and drop an impressive album that, this time around, left Nas impressed. Nas even appeared on a remix of “Let Nas Down” titled “Made Nas Proud.”

For Kendrick, he proved that the success he found with good kid m.A.A.d. city was not an anomaly. Not only did Kendrick live up to the hype, he surpassed it and dropped one of the most impressive rap albums in modern music. To Pimp A Butterly tackles a horde of complex societal issues in a crisp, thematically coherent manner that features distinguished songwriting and experimental production. Let us know which album you think is best below.