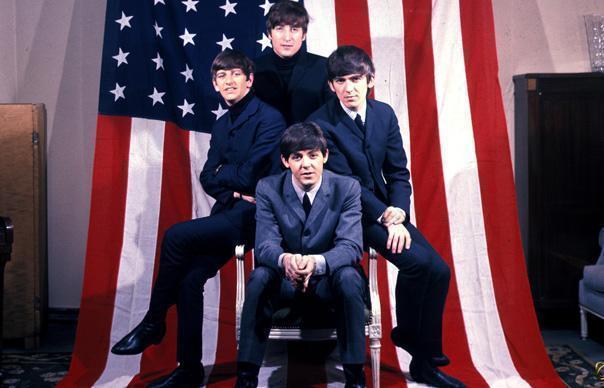

As spiritual and musical reawakenings go, it has to be said that The Beatles’ Indian love affair got off to a shaky start. In Richard Lester’s 1965 film Help!, we see the Fabs become embroiled with a sinister Eastern cult who set out to sacrifice a female Beatles fan to their goddess. While hindsight hasn’t been kind to Help!, it also allows us to get the full measure of the chain of events it would trigger on the musicians at the centre of the enterprise.

- ORDER NOW: The Rolling Stones are on the cover of the November 2021 issue of Uncut

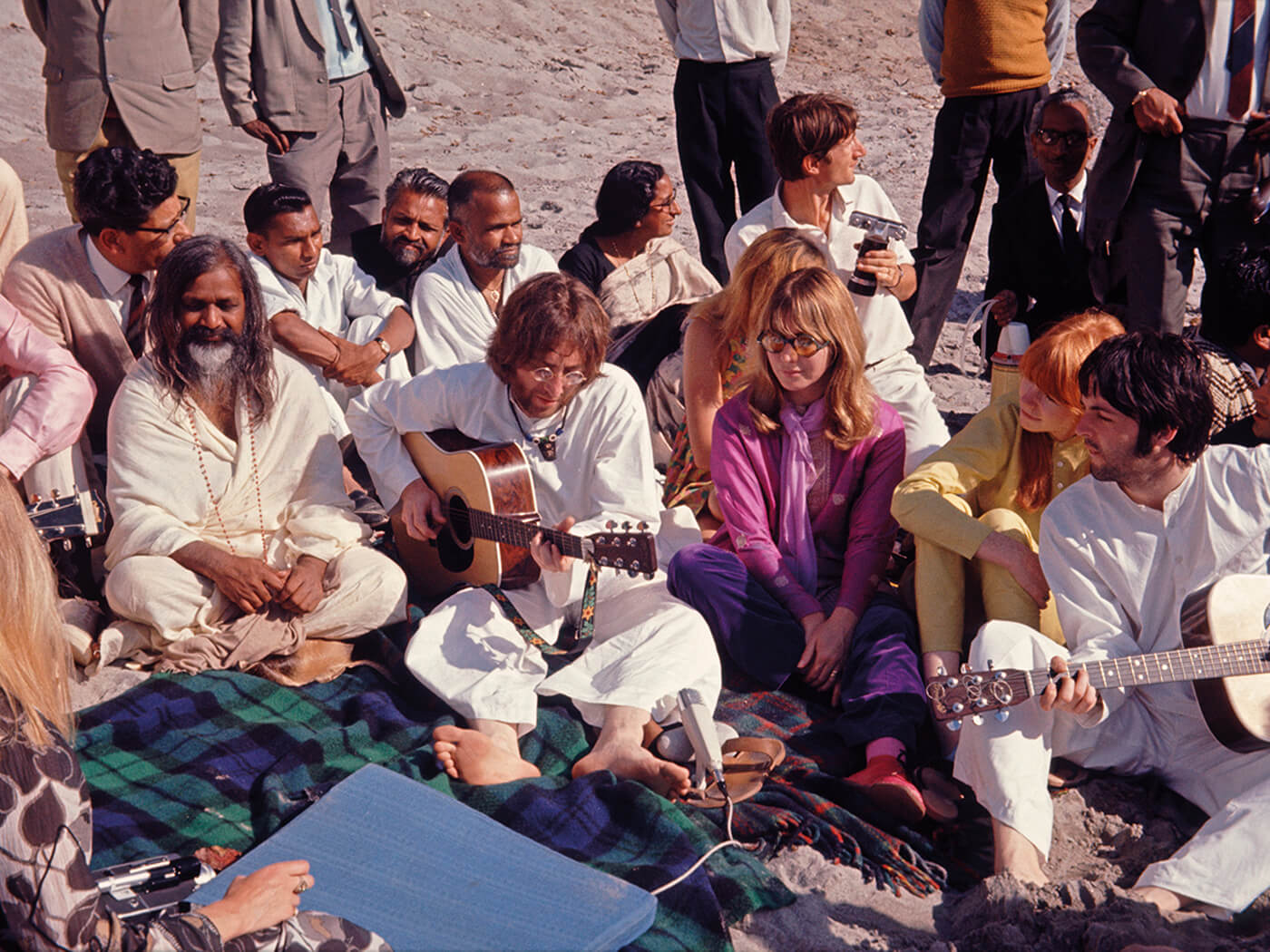

As with his 2005 book The Beatles In India, Ajoy Bose’s directorial debut [co-director Peter Compton] suspends current censoriousness to catapult us to a world where it wasn’t unforgivable to get things wrong about other cultures as long as you were trying to get it right. Early on, it’s the blossoming friendship between George Harrison and Ravi Shankar that provides the main source of warmth. What started with George picking up an unattended sitar on the Help! set fast-forwards to a momentous encounter when Asian Music Circle Founders Ayana and Patricia Angani invited The Beatles for dinner with Shankar at their Hampstead home. Decades later, their son Shankara recalls it was Paul McCartney who seemed out of his depth in comparison to George – who, Pattie Boyd noted, must have known Shankar “in a past life”.

Perhaps for George, Indian music offered a space well away from what must have sometimes felt like John and Paul’s musical fiefdom. Certainly, it massively increased his cultural stock, both within and without The Beatles. Had George not spearheaded The Beatles’ rebirth as spiritual seekers, it’s impossible to conceive of the White Album, most of which was written at the Rishikesh retreat where the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi taught transcendental meditation. Bose manages to locate fellow disciples for vivid recollections set amid the ruins of the once-thriving Ashram, among them teacher Nick Nugent, who excitably recalls a rooftop concert on the Ashram bungalow that predated the more famous one on the Apple building a year later.

Elsewhere, there’s a welcome corrective to pernicious inaccuracies that permeate most accounts of The Beatles’ sudden departure from Rishikesh, with eminent Fabologists Mark Lewisohn and Steve Turner both emphasising the Machiavellian machinations of hanger-on Magic Alex Mardas, who persuaded Lennon that the Maharishi was guilty of sexual impropriety towards a young woman in the Ashram. And even though Lennon wrote Sexy Sadie as they waited for their taxis, subsequent interviews with McCartney and Harrison revealed that both were regretful of the manner in which their retreat ended – Harrison even seeking the Maharishi’s forgiveness.

But perhaps the most pleasing harmonic balance established by The Beatles And India only truly reveals itself near the end, as an array of Indian musicians try to express just how the group’s music impacted upon them. What begins problematically doesn’t have to end that way. Over 50 years later, what survives is gratitude on all sides that The Beatles and the Indian musicians, teachers and fans they met got to be part of each other’s story. Others may put it in more florid terms, but none manage to do so quite as resonantly as musician Neil Mukherjee, who attempts to explain the effect that The Beatles had on him thus: “The world would have been, like, so shit without them.”