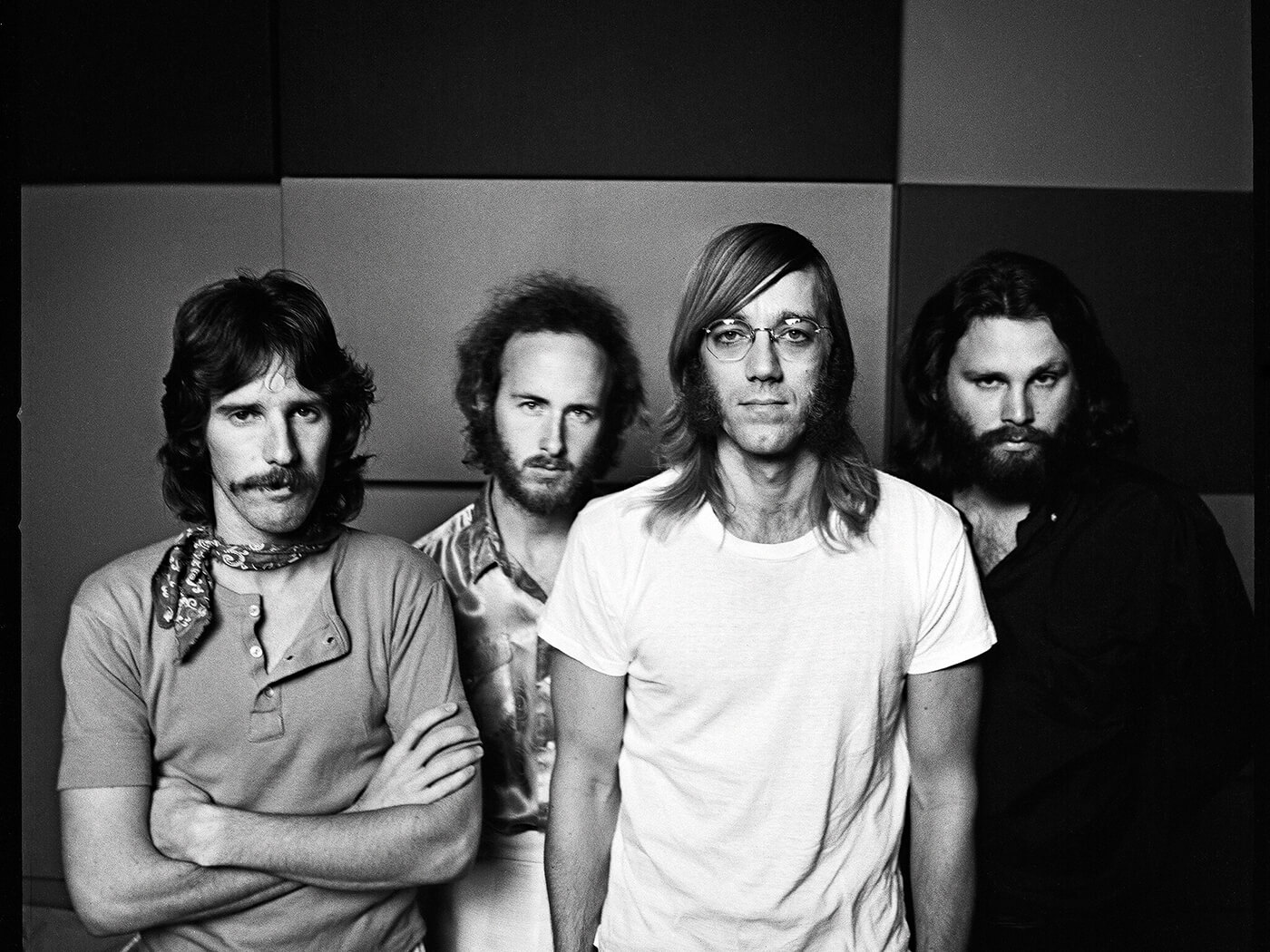

The portents weren’t good. Still reeling from a disastrous gig in New Orleans where Jim Morrison – overweight, heavily bearded and catatonically drunk – had smashed his microphone and stormed off stage during final song “Light My Fire”, The Doors assembled at their rehearsal room at 8512 Santa Monica Boulevard in December 1970 to start work on a new record.

- ORDER NOW: Paul Weller is on the cover in the latest issue of Uncut

With their singer potentially facing six months’ hard labour in a Florida prison, having been found guilty of “indecent exposure and profanity” at their infamous gig in Miami, long-term producer Paul Rothchild having quit, and short on new material, the odds seemed stacked against them. Yet the album which emerged from this seemingly hopeless situation is now widely considered to be The Doors’ defining artistic statement.

A soundscape of the city that spawned it, LA Woman oozes both glamour and seediness, its combination of driving, desert-dry blues and brooding lounge as sleazily enigmatic as its titular heroine, “another lost angel” in the “city of night”. Shot through with a sense of impending doom – five of the ten tracks, eight written by Morrison, are coded farewells – it’s as gripping as fiction, a goodbye to both Los Angeles and the singer’s rock-star alter ego. All set against a musical backdrop that takes the band full circle to their garage roots.

A decade on from the album’s last reissue, this expanded 50th-anniversary edition sheds new light on this most intriguing of records. Newly remastered – once more – by producer Bruce Botnick, the original 49-minute album comes with some serious sonic sparkle. John Densmore’s drums are snappier, Robby Krieger and Ray Manzarek’s intuitive interplay more zingy, Morrison’s boozy baritone more intoxicating than ever.

It’s the two hours of bonus material, however, that really set the pulse racing. Opening with Morrison announcing, “Work in progress, take one”, a demo of “Hyacinth House” recorded at Krieger’s home studio in 1969 is rudimentary but still affecting, the singer’s cryptic lyric – inspired by Greek mythology and hinting at a re-evaluation of his own life – all the more compelling set against just acoustic guitar and Densmore’s congas.

Only discovered by Botnick on an unmarked reel while overseeing the project, a full band version of “Riders On The Storm” is a different beast altogether. Recorded at Sunset Sound Studios earlier in the year, and famously derided as “cocktail music” by outgoing producer Rothchild, it’s slightly pacier than the finished version, Manzarek’s fuzz-tone piano bass and Densmore’s more aggressive drum pattern providing a suitably paranoic backdrop for Morrison’s tale of a hitch-hiking highway killer.

“Part 2” is where we’re really offered a peek behind the creative curtain. With all six musicians (including former Elvis bassist Jerry Scheff and rhythm guitarist Marc Benno) crammed into their cramped basement practice room – Morrison sang his vocals in the bathroom – the songs come charged with a kinetic energy. You can almost feel the sweat dripping off the walls during a 26-minute montage of various takes of “The Changeling”. Beginning with a sadly abandoned scorching instrumental intro, it ebbs and flows from organ-heavy freakout to the James Brown-style soul strut of the finished version, Morrison maintaining energy levels throughout with a series of whoops, grunts and howls. It’s the sound of both band and singer cutting loose, Morrison’s heartfelt hollers of “I’m leaving town on the midnight train!” driven by a desperation to escape the straitjacket of stardom.

A 20-minute flow of various versions of “Love Her Madly” is equally absorbing, Manzarek’s extended keyboard vamp on one take suggesting the myriad pathways this most succinct of pop songs could have taken. If Morrison sounds largely uninterested here, mumbling “lucky nine” as the band attempt another version, he’s on fire during 18 minutes of outtakes for “Riders On The Storm”. “Riding down the trail to Albuquerque/Saddlebags filled with beans and jerky”, he ad-libs jokily in response to Krieger’s “Rawhide”-style guitar noodling between takes, and later announces, “I’m just a dumb singer,” when he’s chided for missing a vocal cue, before drawling, “I’ll come in whenever I feel like it” – still every inch the Lizard King. One version even finds him experiencing a “eureka” moment as he comes up with the notion of starting the song with rainstorm sounds effects. “Hey, that’s a good idea!” he says to himself, having imitated the sound of a thunderclap over the opening bars. It’s a shiver-down-the-spine moment – rock history in the making.

The various takes of “LA Woman” are equally exhilarating. One version climaxes with a frazzled Morrison rasping “Mr Mojo Risin!”, as the band conjure up a blistering outro of overdriven keys, pounding drums and needle-sharp guitar glissandos, while a hypnotically sludgy, 13-minute “Part 3” is as swampy as the bayou. It’s the best of the unreleased material, although a cover of Allen Toussaint’s “Get Out Of My Life, Woman”, a staple of early live shows, runs it close.

In the end, of course, those portents turned out to be true. Jim Morrison never stepped on stage again, and two-and-a-half months after the release of LA Woman, on July 3, 1971, he was found dead in a Paris bathtub, aged 27. On the lonely highways and in the seedy lounge bars of this album, however, he remains, as he sings on “The WASP (Texas Radio And The Big Beat)”, “stoned, immaculate”.