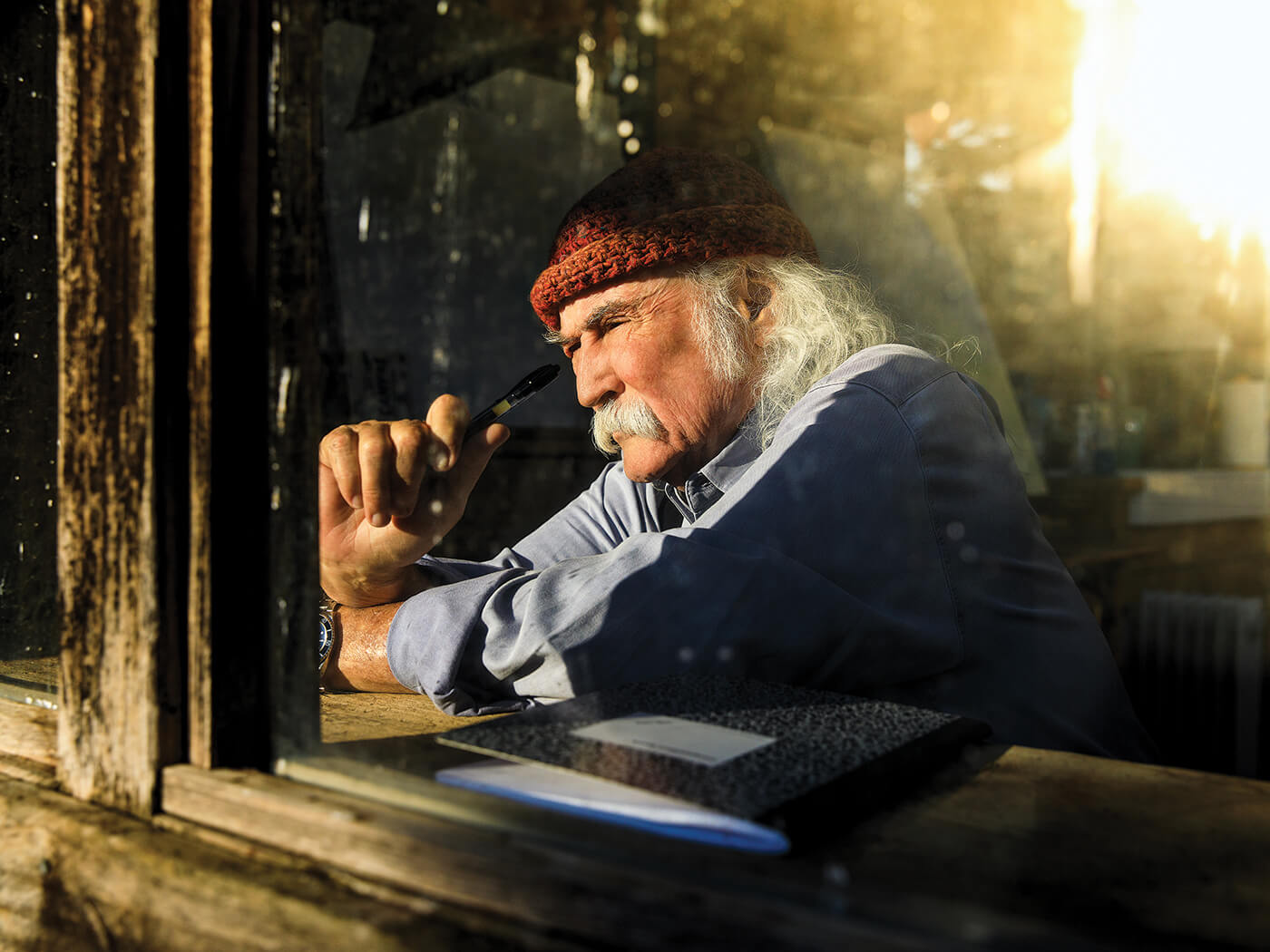

The renewed and reinvigorated Crosby’s twilight productivity continues apace as

he approaches his 80th birthday this August. For Free is his fifth album since Croz, 2014’s comeback after a 20-year absence from the studio, again with the guiding hand of his multi-instrumentalist and producer son James Raymond and the same core of musicians, now dubbed the Sky Trails Band.

- ORDER NOW: Nick Cave is on the cover of the October 2021 issue of Uncut

- READ MORE: Review: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – Déjà Vu: 50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition

Yet, while the record’s 10 tracks are elegantly shaped by players plucked from a younger generation, there are strong contributions of both pen and performance by more veteran figures from the main man’s past too, not to mention a sleeve portrait painted by Joan Baez. The title track first saw service on its writer Joni Mitchell’s 1970 album Ladies Of The Canyon, stripped back here as an intimate piano ballad with Texan singer-songwriter Sarah Jarosz as duet partner.

It’s a number that Crosby has intermittently sung live over the past 50 years, its lyrical eavesdropping simplicity appealing “because I love what it says about the spirit of music and what compels you to play”. That compulsion, to play for free, was the ethos behind the self-financed Croz and the collections that followed, a desire to pursue one’s art regardless

of its commercial potential.

Tapping into that lifelong joy for what he does informs the opening River Rise, co-written by Raymond and Michael McDonald, the latter weighing in with exquisite harmonies. It’s a sweet and gentle evocation of the California-soaked vibes of those days when he, Stephen Stills and Graham Nash first discovered the beauty in the blend of their voices.

Early explorations of what became a signature sound are also recalled on the self-penned I Think I, as are the pitfalls that tended to befall Crosby along the way, examined through older eyes (“They don’t tell you when you arrive/All the things you need to stay alive/There’s no instructions and no map/No secret way past the trap”). It’s tempting, on more than one occasion, to view its maker as a sage-like figure imparting the wisdom of both triumphs and wrong turns.

Crosby is just as confessional and articulate a writer on Shot At Me, a Laurel Canyon guitar-pickin’ resolution to keep to the straight and narrow (“You’ve got to find your lifeline and pick up your thread/And tell your story before you’re dead”). However, don’t be tricked into thinking the album should be filed on the same shelf as motivational guides

or self-help manuals. There remains a rather playful appetite for self-deprecation

here, an endlessly attractive willingness to laugh at one’s own shortcomings and foibles.

It’s not all self-reflection and navel-gazing; For Free is awash with illustrations of Crosby’s talent to tell stories as a detached observer, whether or not he wrote the story himself. The slick, mid-tempo Rodriguez For A Night is cinematically rich in its sketches of outlaws, angels and drugstore cowboys, and would have sat neatly on its composer Donald Fagen’s own solo high-water mark, The Nightfly. Even here, though, Croz the narrator is feasibly singing about a version of his younger playboy persona (“I confess he had some qualities that might attract a foolish girl/An effortless charisma, and a clever way with the world”).

Fagen fashioned the song specifically for Crosby, a showcase for his friend’s often underappreciated jazz phrasing, the laconic punctuation of the vocal mirroring the sharps and flats of the brass melody (also in evidence on the lost love lament Secret Dancer). However, if any one man has the most assured handle on the singer’s strengths, it’s Raymond, assembling eloquent but unobtrusive musical mosaics that fit Dad like a glove.

He’s no slouch as a writer, either, drawing upon what one imagines is eyewitness accounts of the older man’s past indiscretions. Boxes floats along on a wave of, to use a divisive phrase, yacht rock, seemingly at odds with a lyric that touches on recurring struggles (“I’ve tried so often to summon my better angels but they’re over the horizon once again/

I already tried to lock them all away/ Up high where the blood runs thin”).

Raymond is also responsible for arguably the most emotionally affecting song on the album, closer I Won’t Stay For Long (its “one, two, three” count-in the sole contribution of another erstwhile casualty Brian Wilson, but that’s by the by). Inspired by Marcel Camus’s 1959 film Black Orpheus, a retelling of the Greek myth of Orpheus and his attempt to bring his wife Eurydice back from the dead, Crosby inhabits the rawness of the lyric with both the stately grandeur of a Shakespearian thespian and the smoky 3am introspection of Sinatra in his prime.

“I’m standing on the porch like it’s the edge of a cliff/Beyond the grass and gravel lies a certain abyss,” he sings, on what he calls his “painfully beautiful” favourite track on the album. It’s a commanding performance bringing down the curtain on a set of songs that, in the space of an economical 40 minutes, crystallise everything that makes Crosby such an alluring, vital and still relevant force.